Query

This query grew out of a very fun interview I did with a Children’s News program called First Stop News. I had a lovely time talking with the team at First Stop News and am delighted to be part of their holiday program. Here is the link to the interview on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VI8mfuvi43A

However, A viewer commented on my discussion of the date of Christmas, and was unhappy with my comments that the date of Christmas on December 25 is not found in the Bible and may be linked with pagan celebrations of winter solstice. In the interview, I also commented that some people theorize a spring date for the birth of Jesus based on the descriptions shepherds tending their flocks in the Bible. The viewer disputed both these claims: first the viewer addressed the date of Christmas with a theory that a measures of the birth of Christ based on other clues in the Bible, based on the idea that date of John the Baptist’s conception during the feast of Tabernacles. The viewer also addressed the second issue regarding shepherds by pointing out the mild climate of the Middle East, making it feasible for shepherds to be out at this time of year.

The producers of the program asked me to respond, so I wrote them a little essay. I combined my response to them with some other notes I had saved elsewhere, and share the result with you here. As I post this on the last (12th) day of Christmas in 2025, it seemed appropriate to address some quandaries about the date of the first day of Christmas.

Answer

Firstly, I think it is important emphasize that I am a scholar of folklore, and my scholarly interest is in the evolution of the traditions of the festival of Christmas, rather than the theology of Christmas. I rely on my theologian colleagues to debate and present the history of theological arguments for the date of Christmas. There is ample evidence that the festival of Christmas borrows heavily from many non-Christian traditions and sources. Apart from the Christian theological arguments for choosing December 25 as the date of the birth of Christ, the Christmas holiday has most certainly evolved and persisted through many cultural transformations for many reasons in addition to Christianity’s own theological arguments and messages. I am interested in the impact of Christmas as a socially capacious, adaptive, and multicultural festival that draws from many sources. I am not interested in proving or disproving Christian theology. But I am interested in the history of the diverse human cultural interpretations of this holiday.

I’m going to present some thoughts from two other scholars of Christmas. First is Clement Miles, via his book Christmas Customs and Traditions, first published in 1912, republished in 1976. This is one of my favorite sources for Christmas folklore and history, but it does reflect assumptions of a particular era of scholarship that was interested in classical and pre-Christian antecedents of Christian holidays. Secondly, I refer to an eminent contemporary scholar of religion, Andrew McGowan of Yale Divinity School (https://divinity.yale.edu/faculty-and-research/yds-faculty/andrew-mcgowan) who recently published a nice article on the topic of the date of Christmas. McGowan goes into much greater detail about the development of the date of Christmas through the history of Christian theological debate, and I strongly encourage you to read his entire article. I will draw some basic ideas and information from Miles and McGowan to illustrate how this debate has been dealt with by scholars over time. https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/how-december-25-became-christmas/#note03

Both Miles and McGowan, scholars writing more than 100 years apart, provide much more sophisticated and nuanced histories of the details of the emergence of a date for Christmas in the Christian church than I was able to describe in our interview on First Stop News, but both also acknowledge that the dating of Christmas on December 25 is not attested directly in the Gospels and has been the subject of theological debate since the beginning of the church.

Early Christians argued about determining this date. In the meantime, early Christians first approached the development of a festival around the emergent Christmas holiday with caution about potential overlap with a pagan holiday. As time moved on and Christianity extended across Europe, Christians adopted, used, or simply tolerated the customs and symbols of adjacent pagan holidays to their advantage in promoting their own religious message. It is also worth mentioning that not all Christians today celebrate Christmas on December 25th. Eastern Orthodox churches celebrate Christmas on January 6th, based on the Julian calendar.

According to the historian and folklorist Clement Miles, Christmas takes many of its customs and probably its date on the calendar from the pagan Roman festivals of Saturnalia and Kalends. Saturnalia occurred on December 17th and continued for the week following. We can see in these Roman festivals the seeds of many of the cultural and social aspects of the Christmas holiday. Miles says, “The most remarkable and typical feature however, of the Saturnalia was the mingling of all classes in a common jollity”, which could include feasting and gift giving.”

The Roman festive season continued into the celebration of Kalends, the New Year, when further feasting, spending, gift-giving, parading, and freedom from work prevailed. These customs were so popular and ingrained in Roman life, that early fathers of the Christian church took pains to condemn the practice of these holidays. In a sermon attributed to St. Augustine of Hippo but likely composed in the sixth century, the saint says, “Now as for them who on those days observe any heathen customs, it is to be feared that the name of Christian will avail them nought [….] For he who on the Kalends shows any civility to foolish men who are wantonly sporting, is undoubtedtly a partaker in their sin.” Participating in Kalends celebrations was formally forbidden for Christians by a church council in Constantinople in 692.

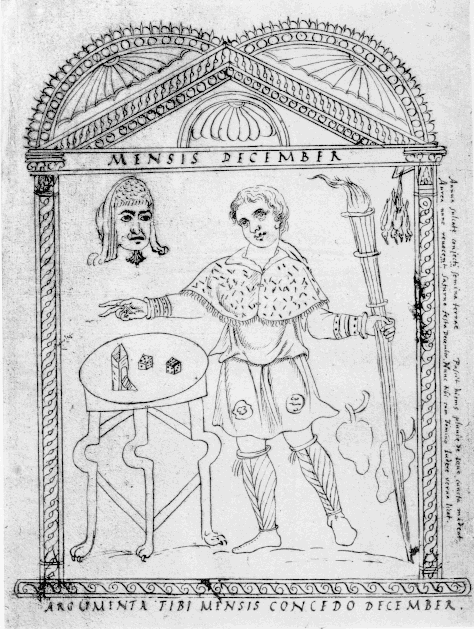

But amidst this rejection of the indulgent aspects of the Roman pagan feasts, Christian observance of the birth of Christ had begun to take root around the same time in the calendar. Clement Miles says, “The first mention of a Nativity feast on December 25th is found in a Roman document known as the Philocalian Calendar, dating from the year 354 […] In 567 the Council of Tours had declared the Twelve Days, from Christmas to Epiphany, a festal tide.” The choice of this date for the celebration of the birth of Christ does not stem from any relationship to the Gospels, as there is no mention of a specific date for Christmas. *This image is of a 17th century manuscript source of the Philcolian Calendar from the Vatican Library(cod. Barberini lat. 2154) which was thought to be copied from a Carolingian copy, Codex Luxemburgensis, a copy of the orginial Roman document.

It is possible that December 25th was chosen to provide an alternative to another pagan celebration on that date the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or the birth of the Invincible Sun, a holiday first celebrated by order of Emerpor Aurelian during his reign from 270-275. Christians may have decided to co-opt this pagan celebration of a sun god, occurring near the winter solstice, to highlight their celebration of the birth of their own “light of the world”, Jesus Christ.

In the eyes of Clement Miles and scholars of his era, these Roman Pagan festivals, Saturnalia and Kalends, and Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, provided an antagonism to the morals of Christianity, but also an opportunity for early Christians. By choosing to celebrate their religious holiday in the same part of the year, Miles believed they probably could could appropriate the momentum of festivity, the symbols of light, and the generosity and excitement of popular pagan celebration and offer an alternative religious observance that highlighted the appearance of their new holy figure into a very old Roman world. Miles says:

“What more natural that that the Church should choose this day to celebrate the rising of her Sun of Righteousness with healing in His wings, that she should strive thus to draw away to His workshop some adorers of the god whose symbol and representative was the earthly sun! There is no direct evidence of deliberate substitution, but at all events ecclesiastical writers soon after the foundation of Christmas made good use of the idea that the birthday of the Saviour had replaced the birthday of the sun.” (Clement Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions. Dover Publications Inc, New York: 1976 pg 23-24).

Miles then refers in a footnote to theories of dating the birth through other scriptural information, referencing another scholar (L Duchesne, “Christian Worship: Its Origin and Evolution” Eng. Trans. Revised Edition. London: 1912). Miles is also nuanced in weaving the cause and effect of these dates together, clearly suggesting influence of Roman paganism on the Christmas festival and the pros and cons early Christians saw in aligning their holiday to this pagan event.

The recent article by McGowan published in Biblical Archaeology provides a very detailed overview of many additional early Christian conversations and debates contributing to the determination of the Christmas holiday and its date. He addresses several theological theories of Jesus’s birth date as calculated in relation to other events in the Bible. Here he discusses one approach that early Christians took in establishing a date for Christmas: “Around 200 C.E. Tertullian of Carthage reported the calculation that the 14th of Nisan (the day of the crucifixion according to the Gospel of John) in the year Jesus diedc was equivalent to March 25 in the Roman (solar) calendar.9 March 25 is, of course, nine months before December 25; it was later recognized as the Feast of the Annunciation—the commemoration of Jesus’ conception.10 Thus, Jesus was believed to have been conceived and crucified on the same day of the year. Exactly nine months later, Jesus was born, on December 25.”

But McGowan also addresses the theory of overlap and influence with other pagan solar festivals like Saturnalia, as Miles did over a century ago. McGowan is more critical of the attributions of influence by Roman pagan sources, and he favors sourcing the date from some of these internal Christian theological theories. But he does not rule out the influence of pagan festivals on the development of the holiday, as he says here:

“In the end we are left with a question: How did December 25 become Christmas? We cannot be entirely sure. Elements of the festival that developed from the fourth century until modern times may well derive from pagan traditions. Yet the actual date might really derive more from Judaism—from Jesus’ death at Passover, and from the rabbinic notion that great things might be expected, again and again, at the same time of the year—than from paganism. Then again, in this notion of cycles and the return of God’s redemption, we may perhaps also be touching upon something that the pagan Romans who celebrated Sol Invictus, and many other peoples since, would have understood and claimed for their own, too.”

How December 25 Became Christmas How did December 25 come to be Christmas? The earliest mention of December 25 comes from a mid-fourth-century Roman almanac. www.biblicalarchaeology.org

Clearly, these debates have been going on for a long time!

Lastly, As for the shepherds watching their flocks by night – this is a theory often mentioned by people who favored a spring date, but the differences in climate do make the reference to shepherds as a marker of time of year unreliable. Even McGowan mentions this in his article: “The biblical reference to shepherds tending their flocks at night when they hear the news of Jesus’ birth (Luke 2:8) might suggest the spring lambing season; in the cold month of December, on the other hand, sheep might well have been corralled. Yet most scholars would urge caution about extracting such a precise but incidental detail from a narrative whose focus is theological rather than calendrical.”

I wanted to mention the shepherd-spring date-theory as something people discussed in debates of the date. While the activities of the shepherds can’t tell us as much as we’d like, it certainly is interesting to think about the agricultural cycles that both the characters near Bethlehem may have been engaging in during the first century AD, as well as the agricultural cycles that Christians interpreted from the story based on their own lived experiences in far flung places around the world.

I appreciate your lens on this unfogged by dogma. I regret that there is a population so utterly convinced that knowing dates is essential to spirituality that they would defend a date. Yes, your cultural perspective stands up much better, and I’m just grateful that Christ wasn’t born in the southern hemisphere. Well said.

Hello! I was the commenter who saw the video and made the corresponding comments that spurred this blog response.

First, thank you for not only taking the time to respond, but doing so with a thoroughly researched response. I am very much aware that you could have rolled your eyes and moved on, especially given that it was a news program aimed at kids. Instead you have provided those viewers and your readers with a complex and nuanced approach to a topic that merits such time and detail. Most importantly, you are showing these young viewers (including my young children) that discourse can happen in a calm and educational manner which often doesn’t happen in today’s divisive world. Thank you again.

The influence of pagan festivals on the development of Christmas over time was never in question; what was in question, and what sparked my response, is the presentation of the December date as arbitrary or simply a response to those pagan festivals. As you have rightly shown here, and as I noted in my comments, for some the date is not arbitrary, even if that date has been debated over the years. This perspective was not included in the initial reporting. In fact, the one-sided presentation was incorrectly presented as fact along with a “shock and awe” factor.

For those who don’t quite understand why a date is important enough to warrant such an important dialogue and thoroughly researched response such as yours, know that questioning a date’s validity has larger consequences, especially with young people. If the date of Christmas is seen as arbitrary and without reason, then that logic could spread to the rest of the faith, calling into question the entire religion itself. Taking the time to combat such understanding and show that these beliefs are not arbitrary is, in my opinion, worth the effort and dialogue.

Thank you again Professor.